Zeyneb Sayılgan, Ph.D.

I return often to an important event from the very beginning of Islamic history, because it refuses to let me give in to despair. At a time when Muslim immigrants and refugees are routinely dehumanized and demonized across Europe and the United States—reduced to statistics, threats, or political tools—this story insists on another possibility. It reminds me that Christian–Muslim relations did not begin with fear or violence, but with protection, hospitality, and a shared reverence for God, Jesus, and Mary.

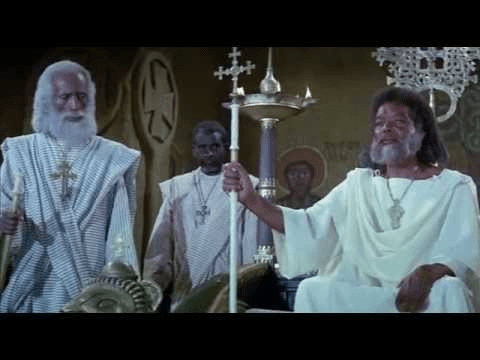

In the seventh century, Prophet Muhammad advised persecuted Muslims to leave Mecca and seek refuge across the Red Sea in Christian Abyssinia (modern day Ethiopia/Eritrea). That kingdom was ruled by a just Christian king known in Islamic sources as the Negus. When envoys from Mecca arrived demanding their return, the king did something remarkable: he listened. He did not judge before hearing their story. He invited the Muslims to speak for themselves. Ja‘far ibn Abi Talib, representing the refugees, recited verses from the Qur’an about Mary and Jesus. According to the accounts, the king wept and declared, “The message of your Prophet and that of Jesus came from the same source.”

That sentence still matters. It tells me that shared belief in one God, and a shared love for Jesus and his mother Mary, created a bond strong enough to overcome fear of the religious “other.” The king did not deny theological differences. Christians and Muslims clearly disagreed on the nature of Jesus and the Divine. Yet those differences did not prevent solidarity. Muslims affirmed common values—justice, care for the poor, protection of the weak, love of neighbor, and the spiritual equality of men and women. This was an early model of interreligious integrity: affirming sameness and difference alike, without coercion or compromise.

This posture feels painfully relevant today. Too often, Muslim refugees are judged before they are heard. In public debates on immigration, they remain objects of conversation rather than participants in it. I see policies formed without listening to the people whose lives are most affected. The Abyssinian king offers a corrective: deep listening as an act of faith. Judging people without knowing their story is unacceptable. To lift up marginalized voices is not charity; it is justice.

Equally striking is what the king did not do. He did not approach the refugees with a utilitarian mindset. He refused the bribes offered by the Meccan elite. He did not ask what benefit these refugees would bring to his kingdom, or what burdens they might impose. He acted out of faith conviction, grounded in the dignity of human beings. In our time, immigration debates often begin with calculations—economic gain, political risk, social cost. While such considerations matter, they cannot be the starting point for people of faith. Human beings are not commodities, and their worth cannot be measured by usefulness.

The Negus also rejected the logic of reciprocity. He did not say, “I will protect you if your people protect mine.” Today, I hear arguments that Western countries should welcome Muslim refugees only if Muslim-majority countries treat Christian minorities well. Justice for one group, however, cannot be conditional on the behavior of another. Refugees cannot be held hostage to the politics of their governments. Faithfulness demands moral clarity, not transactional generosity.

Hospitality stands at the heart of this encounter. In both Christian and Islamic traditions, hospitality is not optional. Jesus’ command to love one’s neighbor as oneself leaves no room for exclusion. The Qur’an similarly teaches that God has already shown hospitality to all humanity, providing sustenance and shelter during our temporary dwelling on earth. To welcome the stranger, then, is to mirror divine mercy. Muslim scholar Bediüzzaman Said Nursi captures this attitude succinctly when he writes, “The mercy of faith embraces every creature.” Here, faith is expressed not through exclusion, but through responsibility for the other—especially where power, fear, or political interests would otherwise push toward exclusion.

The king granted the Muslims asylum, freedom of religious practice, and protection from persecution. The Muslims, in turn, pledged loyalty to their new home. Some even converted to Christianity; others remained Muslim. Conversion happened on both sides, including, according to Islamic tradition, the king himself. These accounts were preserved honestly, without embarrassment or censorship, revealing a confidence grounded in faith rather than fear.

The Muslim refugees did not isolate themselves. They contributed economically, defended Abyssinia in times of war, and prayed for Christian victory against rebels. They obeyed local laws and refrained from undermining their hosts. Islamic jurists later pointed to this example to argue that integration into a non-Muslim society is not only permissible but necessary. Education, language acquisition, and civic participation were seen as religious duties. To live with dignity meant becoming an asset to the broader society.

Muslims can look back with pride on a long history of migration and contribution—from advances in medicine and philosophy to art, architecture, and agriculture. These achievements were not despite faith, but because of it. Yet the goal of participation was never domination or forced conversion. As the Abyssinian model shows, Christians and Muslims freely shared their spiritual treasures while respecting personal choice.

When people today insist on an “us versus them” narrative, they suffer from what theologians call historical amnesia. All faith communities began at the margins. All were once vulnerable, displaced, and dependent on the mercy of others. The first Muslim community, by its own telling, survived because a Christian king chose compassion over fear. Many Muslim scholars argue that without this protection, Islam itself might not have endured.

This is why I refuse narratives that exclude Muslims from Western moral history. The story of Abyssinia belongs to all of us. It challenges both receiving societies and immigrant communities. It calls hosts to listen deeply, reject dehumanization, and practice hospitality rooted in faith. It calls newcomers to engage, contribute, and honor the laws and values of their new homes without surrendering their identity.

This holy encounter is not just a memory of a distant past, but a vision of a world still to come—a world built by sincere people of faith who care more about love for humanity than the triumph of their own tribe or theology. I hold onto that hope. In an age of walls and suspicion, the image of Mary—revered by both Christians and Muslims—still stands between us, calling us back to our shared humanity.

A version of this essay was published The Living Church

The German piece appeared on IslamiQ

Zeyneb Sayılgan, Ph.D., is the Muslim Scholar at the Institute for Islamic, Christian and Jewish Studies in Baltimore. Her research focuses on Islamic theology, ethics and spirituality as articulated in the writings of Muslim scholar Bediüzzaman Said Nursi (1876-1960). Her other areas of interest are Christian-Muslim relations and the intersection of religion and migration. Zeyneb’s personal experience of growing up in Germany as the daughter of Muslim immigrants from Türkiye informs her academic work and engagement in Christian-Muslim relations. Her articles have been published in The Guardian, Religion News Service, U.S. Catholic, The Living Church and German and Turkish outlets. To read her work and listen to her podcast visit her blog.

Discover more from Zeyneb Sayılgan

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.